Modern opportunities for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: the role of the fixed combination netupitant + palonosetron

Dunaieva I.P., Kryvoshapka O.V., Doroshenko O.M., Shapoval O.M., Pautina O.I.

Summary. The article summarises current views on the pathogenesis of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) and substantiates the expediency of using combined antiemetic strategies in patients receiving moderately and highly emetogenic chemotherapy. The roles of peripheral and central mechanisms in the formation of the emetic reflex, involving serotonin 5-HT₃ and neurokinin-1 (NK1) receptors, are considered, underscoring the need for a multicomponent, pathogenetically targeted approach to CINV prophylaxis. Particular attention is paid to the fixed combination of netupitant and palonosetron (NEPA) as a modern means of antiemetic prophylaxis. The pharmacological and pharmacokinetic properties of NEPA components, their synergistic interactions, and their clinical advantages, in particular, effective control of both acute and delayed phases of CINV, are analysed. Data from randomised clinical studies and meta-analyses are presented that confirm NEPA’s high clinical efficacy, safety, and convenience compared with traditional aprepitant-containing regimens. The place of the fixed combination netupitant + palonosetron in current international clinical recommendations from Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer / European Society for Medical Oncology (MASCC / ESMO) and American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) as one of the agents of choice for CINV prophylaxis is shown, which contributes to increased patient adherence to treatment and to the optimisation of supportive therapy in oncology practice.

Received 22.01.2026

Accepted 6.02.2026

DOI: 10.32471/clinicaloncology.2663-466X.35373

INTRODUCTION

CINV are among the most common and, at the same time, the most burdensome complications of modern anticancer treatment. According to clinical observations and multicenter studies, the incidence of CINV ranges from 30 to 90% and depends on the emetogenic potential of the chemotherapy regimen, the drug dose, the route of administration, and individual patient characteristics. It should be noted that pronounced emetogenic potential is typical of older cytotoxic agents, including platinum compounds. In contrast, modern agents such as monoclonal antibodies are characterised by moderate or even low emetogenicity. Nevertheless, despite significant progress in the development and implementation of antiemetic therapies, the problem of effective control of nausea and vomiting remains relevant in everyday oncology practice [1–6].

The clinical significance of CINV goes far beyond mere symptomatic discomfort. Persistent or uncontrolled nausea and vomiting substantially reduce patients’ quality of life, disrupt nutrition and water–electrolyte balance, and contribute to the development of asthenic syndrome, dehydration, and metabolic disorders. In a number of cases, severe manifestations of CINV become a reason for reducing chemotherapy drug doses, postponing subsequent courses, or even complete refusal to continue anticancer therapy, which directly and negatively affects treatment efficacy and oncological prognosis [2, 5–6].

A particular clinical problem is the delayed phase of CINV, which develops 24–120 hours after chemotherapy administration and is often less controllable compared with the acute phase. It is delayed nausea that is most often perceived by patients as the most exhausting, responds poorly to standard antiemetic regimens, and significantly reduces adherence to treatment. At the same time, clinical studies indicate that insufficient control of the acute phase of CINV substantially increases the risk of delayed symptoms in the subsequent days [2, 6].

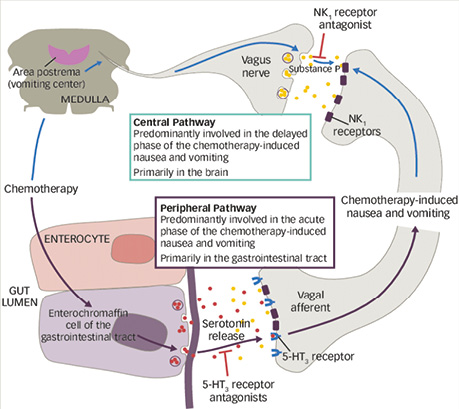

Current views on the pathogenesis of CINV are based on an understanding of the complex interactions between peripheral and central mechanisms, in particular the roles of serotonin 5-HT3 receptors and the NK1 receptor for substance P. This determines the need for a multicomponent approach to CINV prevention, with simultaneous impact on different links in the emetic reflex pathway. In this context, combined antiemetic regimens combining 5-HT3 and NK1 receptor antagonists with corticosteroids are considered the most pathogenetically substantiated. The development of CINV involves interconnected peripheral and central signalling pathways that engage serotonin 5-HT3 and NK1 receptors (Fig. 1) [2, 6–7].

Fig. 1. Peripheral and central mechanisms of the development of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. The peripheral pathway is realised through the release of serotonin from enterochromaffin cells of the gastrointestinal tract, with activation of 5-HT3 receptors of afferent fibres of the vagus nerve and predominantly determines the acute phase of symptoms. The central pathway is associated with activation of NK1 receptors of substance P in brainstem structures, including the area postrema, and plays a leading role in the development of the delayed phase of nausea and vomiting. 5-HT3 and NK1 receptor antagonists block the respective links of pathogenesis [6]

Given the increasing use of highly and moderately emetogenic chemotherapy regimens, as well as the increasing duration and intensity of oncological treatment, the search for optimal, effective, and patient-convenient antiemetic strategies is a highly relevant task of modern oncology. Fixed combinations of antiemetic drugs are of particular interest in this regard, as they enable greater efficacy of CINV prophylaxis, simplify the treatment regimen, and improve patients’ adherence to therapy [8–10].

Considering the multifactorial pathogenesis of CINV, effective prophylaxis of this complication requires simultaneous effects on both peripheral and central mechanisms of formation of the emetic reflex. Current clinical recommendations from leading international oncology societies emphasise the expediency of using combined antiemetic regimens comprising serotonin 5-HT3 receptor antagonists and NK1 receptor antagonists, in combination with corticosteroids, especially in patients receiving moderately or highly emetogenic chemotherapy [1, 6, 11].

Among the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist class, palonosetron attracts particular attention — a second-generation agent characterised by high receptor affinity, a long elimination half-life, and proven efficacy in controlling both the acute and, in part, the delayed phase of nausea and vomiting. At the same time, NK1 receptor antagonists play a key role in the prophylaxis of delayed CINV — among them, netupitant is distinguished by prolonged action and the ability to effectively block the central mechanisms of vomiting associated with substance P [9, 12, 13].

Beyond CINV, both NK1 receptor antagonists and 5-HT3 receptor antagonists are used to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting, and pharmacogenetic determinants of response to 5-HT3 antagonists have been described [14, 15].

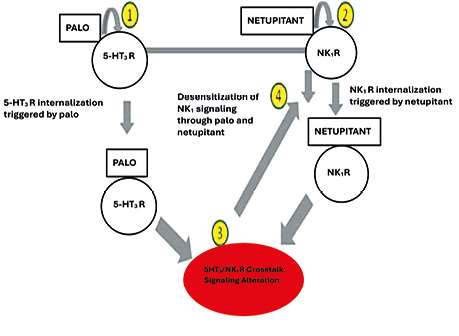

The pharmacological rationale for combining NEPA is based on their complementary mechanisms of action, which provide comprehensive control of all phases of CINV. Therefore, the fixed combination of these drugs is considered one of the most promising and clinically substantiated approaches to CINV prophylaxis in modern oncology practice. The pharmacodynamic synergism of NEPA is realised through interactions with serotonin 5-HT3 and NK1 receptors, with receptor internalisation and modification of intracellular signalling (Fig. 2) [9, 12, 16].

Fig. 2. Pharmacodynamic mechanisms of the synergistic action of netupitant and palonosetron. Palonosetron induces internalisation and desensitisation of serotonin 5-HT3 receptors, whereas netupitant causes blockade and internalisation of NK1 receptors of substance P. Crosstalk between 5-HT3 and NK1 signalling pathways leads to inhibition of central and peripheral mechanisms of the emetic reflex, providing control of both the acute and delayed phases of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting [16]

Pharmacological properties of NEPA components

Palonosetron belongs to the second-generation serotonin 5-HT3 receptor antagonists and is characterised by several pharmacological advantages compared with representatives of the previous generation (ondansetron, granisetron, tropisetron). Its antiemetic action is due to a highly selective, prolonged blockade of 5-HT3 receptors, which play a key role in triggering the emetic reflex during chemotherapy. A feature of palonosetron is an exceptionally high affinity for 5-HT3 receptors, which is several-fold higher than that of other setrons. In addition, the drug demonstrates a unique mechanism of interaction with the receptor — an allosteric binding that induces internal invagination of the receptor complex, ensuring prolonged inhibition of serotonin-dependent signalling even after a decrease in the drug’s plasma concentration [7, 12].

From a pharmacokinetic perspective, palonosetron has a long elimination half-life of about 40 hours. This characteristic substantially exceeds that of other 5-HT3 receptor antagonists and enables a stable antiemetic effect throughout the entire acute phase of CINV, as well as partial influence on early manifestations of the delayed phase. Palonosetron is predominantly metabolised in the liver, forming inactive metabolites, and is eliminated by the kidneys and the intestine, reducing the risk of accumulation in patients with moderate renal impairment [12, 17].

Netupitant is a highly selective NK1 receptor antagonist of substance P, one of the key neurotransmitters involved in the central mechanisms underlying the acute and, first of all, the delayed phase of CINV. Blockade of NK1 receptors in structures of the central nervous system, particularly in the vomiting trigger zone and the nucleus tractus solitarius, inhibits the integration of emetic impulses regardless of their peripheral origin [7, 12, 13].

The pharmacokinetic profile of netupitant is a key advantage. The drug is characterised by an exceptionally long elimination half-life, which averages about 96 hours, substantially exceeding the corresponding indicators of other representatives of the NK1 antagonist class. Due to this, netupitant provides continuous blockade of NK1 receptors throughout the entire period of increased risk of developing delayed nausea and vomiting after chemotherapy [9, 12].

Netupitant is well absorbed when administered orally, has a high degree of plasma protein binding, and actively penetrates the blood–brain barrier, which is critically essential for the realisation of its central mechanism of action. Metabolism of the drug occurs predominantly via the CYP 3A4 enzyme system, leading to the formation of pharmacologically inactive metabolites, which are eliminated predominantly via bile [12, 18].

Due to its prolonged action and central mechanism of influence, netupitant effectively controls the delayed phase of CINV, reduces the need for additional antiemetic agents, and contributes to increased patients’ adherence to anticancer treatment [9, 12, 19].

The combination of NEPA, as a fixed-dose NEPA, enables a synergistic effect by simultaneously blocking peripheral serotonin-mediated mechanisms and central NK1-dependent pathways of vomiting. The complementarity of their pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties provides effective control of both the acute and delayed phases of CINV with a minimal dosing regimen [9, 12]. The fixed oral combination of NEPA was first approved for clinical use in the USA by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in October 2014 for the prevention of both acute and delayed nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy [20]. In the European Union, this fixed combination received marketing authorisation from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in May 2015, which also allowed its use in the prevention of nausea and vomiting associated with both highly and moderately emetogenic chemotherapy regimens in adults [18]. This combination is registered in Ukraine as hard capsules, 300/0.5 mg; 1 hard capsule contains 300 mg of netupitant and 0.56 mg of palonosetron hydrochloride, equivalent to 0.5 mg of palonosetron [18, 21]. Manufacturer of the medicinal product: Helsinn Birex Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Ireland. The convenience of this medicinal product for patients should be noted, as a single hard capsule is taken approximately 1 hour before the start of each chemotherapy cycle [21, 22].

CLINICAL EFFICACY OF THE NETUPITANT + PALONOSETRON COMBINATION: CURRENT CLINICAL TRIAL DATA

The clinical efficacy of the fixed combination NEPA has been convincingly demonstrated in a series of randomised, multicentre phase III studies, the results of which served as the basis for including the drug in international clinical recommendations. One of the key studies in this direction compared the efficacy of NEPA in combination with dexamethasone with that of palonosetron + dexamethasone in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy. The authors demonstrated statistically significantly higher complete response rates in the NEPA group not only in the acute phase but also in the delayed and overall phases of CINV, emphasising the key role of NK1 receptor blockade in long-term symptom control. Further confirmation of these results was obtained in the extensive randomised study, which included more than 1,400 patients receiving both moderately and highly emetogenic chemotherapy regimens. In this study, NEPA + dexamethasone significantly outperformed palonosetron + dexamethasone in complete response and absence of clinically significant nausea across all time phases. It is important that the advantages of NEPA were maintained across multiple consecutive cycles of chemotherapy, which is clinically significant given the tendency for CINV to intensify with repeated courses of treatment [9, 12, 23, 24].

A comparison of NEPA with aprepitant-containing regimens was conducted in a randomised trial evaluating the efficacy of single-dose oral NEPA + dexamethasone versus the standard three-day regimen of aprepitant + granisetron + dexamethasone in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy. The results showed that NEPA was not inferior to the aprepitant-containing regimen in complete response and, in the delayed and overall phases, showed a tendency toward better vomiting control and less need for «rescue» medications, while substantially simplifying the prophylaxis regimen [10, 19].

Beyond comparisons with standard regimens, subsequent years have yielded data on the efficacy of NEPA in specific and clinically challenging patient populations. Thus, in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, the NEPA combination demonstrated significantly higher rates of complete control of nausea and vomiting than monotherapy with 5-HT3 receptor antagonists. Additional studies have reported favourable efficacy and safety of NEPA in patients receiving R-CHOP for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, in high-dose conditioning regimens such as BEAM prior to hematopoietic cell transplantation, and during (neo)adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin. The advantage of NEPA was statistically significant in the acute, delayed, and overall phases, confirming the universality of its mechanism of action even in extremely vulnerable oncology patients [25–30].

Review papers and meta-analyses of recent years, in particular the summarising analysis, as well as new analytical publications of 2024–2025, confirmed that NEPA is at least not inferior to aprepitant or fosaprepitant-based regimens in key clinical endpoints and, in certain aspects, control of delayed nausea and reduction of the need for rescue therapy demonstrates a potential advantage. The authors pay particular attention to the simplicity of the NEPA administration regimen as a factor that positively affects adherence to antiemetic prophylaxis in real clinical practice [9, 10, 31].

PLACE OF NEPA IN CURRENT CLINICAL RECOMMENDATIONS

According to modern international guidelines, prophylaxis of CINV should be based on the emetogenic potential of the anticancer regimen and include a combined approach affecting key pathogenetic mechanisms of the emetic reflex. In this context, leading professional oncology societies recommend the use of a combination of an NK1 receptor antagonist, a serotonin 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, and a corticosteroid (dexamethasone) as the standard for CINV prophylaxis in highly emetogenic and specific moderately emetogenic chemotherapy regimens [1, 6, 11].

In particular, the recommendations of the MASCC / ESMO clearly define the need to include NK1 receptor antagonists in antiemetic regimens for patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy, as well as for those receiving anthracycline- and cyclophosphamide-based chemotherapy. The MASCC / ESMO guideline updates emphasise that combination therapy makes it possible to substantially improve control not only of vomiting but also of clinically significant nausea, especially in the delayed phase [1].

A similar approach is reflected in the guidelines of the ASCO, which recommend combined antiemetic regimens using an NK1 antagonist, a 5-HT3 antagonist, and dexamethasone as first-line therapy for highly emetogenic regimens and for specific variants of moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. The ASCO recommendations emphasise adherence to prophylaxis regimens throughout the entire period of CINV risk, including the delayed phase [11].

Within these recommendations, the fixed combination NEPA is considered a clinically appropriate and practically convenient option for implementing guideline-concordant antiemetic prophylaxis. The combination of an NK1 receptor antagonist and a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist in a single dosage form simplifies the treatment regimen to a single intake per chemotherapy cycle, which is of fundamental importance for increasing patient adherence to therapy, especially in outpatient settings [9, 19]. From a health-economic perspective, a cost-effectiveness analysis suggested that NEPA may be a cost-effective prophylactic option in highly emetogenic chemotherapy settings [32].

From the perspective of current MASCC / ESMO and ASCO recommendations, NEPA meets the key requirements for effective CINV prophylaxis: it provides control of both acute and delayed phases, corresponds to the evidence base of international clinical studies, and combines high clinical efficacy with simplicity of use, which makes it an optimal choice in real oncology practice [1, 9, 11].

CONCLUSIONS

1. The fixed combination netupitant + palonosetron is a modern, scientifically substantiated agent for the prophylaxis of CINV, the efficacy and safety of which are confirmed by the results of randomised clinical studies and real-world clinical practice data. The combination of an NK1 receptor antagonist and a new-generation 5-HT3 receptor antagonist provides comprehensive, pathogenetically substantiated control of both the acute and delayed phases of CINV, which is a key factor in preserving the quality of life of oncology patients.

2. Due to the complementary pharmacological properties of the components, the prolonged action of palonosetron and the high selectivity of netupitant, the fixed combination netupitant + palonosetron makes it possible to achieve a stable antiemetic effect throughout the entire period of risk of developing CINV. The possibility of single use of the drug per chemotherapy cycle significantly simplifies the prophylaxis regimen, increases patient adherence to treatment, and reduces the need for additional antiemetic agents.

3. An essential advantage in the management of CINV is a reduced risk of drug interactions and a favourable tolerability profile, which is of particular importance in patients with polymorbid pathology and during multi-cycle chemotherapy. Use of the fixed combination contributes to optimising antiemetic therapy, reducing breakthrough nausea and vomiting, and increasing the overall efficacy of anticancer treatment.

4. Conformity of netupitant + palonosetron with modern international clinical recommendations of MASCC / ESMO and ASCO allows this drug to be considered one of the agents of choice for prophylaxis of CINV in patients receiving moderately and highly emetogenic chemotherapy, as part of standardised supportive therapy regimens in oncology practice.

REFERENCES

1. Herrstedt, J., Clark-Snow, R., Ruhlmann, C. H., Molassiotis, A., Olver, I., Rapoport, B. L., … Scotté, F. (2024). 2023 MASCC and ESMO guideline update for the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. ESMO Open, 9(2), 102195. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.102195.

2. Gupta, K., Walton, R., & Kataria, S. P. (2021). Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: Pathogenesis, recommendations, and new trends. Cancer Treatment and Research Communications, 26, 100278. doi: 10.1016/j.ctarc.2020.100278.

3. Wang, Y., Zheng, R., Wu, Y., Liu, T., Hao, L., Liu, J., … Guo, Q. (2025). Risk prediction model for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in cancer patients: a systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 168, 105094. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2025.105094.

4. Karthaus, M. (2023). Chemotherapieinduzierte Nausea und Emesis. HNO, 71(7), 473–484. doi: 10.1007/s00106-023-01315-9. [Karthaus, M. (2023). Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. HNO, 71(7), 473–484. German].

5. Heckroth, M., Luckett, R. T., Moser, C., Parajuli, D., & Abell, T. L. (2021). Nausea and vomiting in 2021: a comprehensive update. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 55(4), 279–299. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001485.

6. Navari, R. M., & Aapro, M. (2016). Antiemetic prophylaxis for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. The New England Journal of Medicine, 374(14), 1356–1367. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1515442.

7. Zhong, W., Shahbaz, O., Teskey, G., Beever, A., Kachour, N., Venketaraman, V., & Darmani, N. A. (2021). Mechanisms of nausea and vomiting: current knowledge and recent advances in intracellular emetic signalling systems. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(11), 5797. doi: 10.3390/ijms22115797.

8. Scotté, F. (2025). Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: can we do better? Current Opinion in Oncology, 37(2), 158–162. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000001114.

9. Aapro, M., Jordan, K., Scotté, F., Celio, L., Karthaus, M., & Roeland, E. (2022). Netupitant-palonosetron (NEPA) for preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: from clinical trials to daily practice. Current Cancer Drug Targets, 22(10), 806–824. doi: 10.2174/1568009622666220513094352.

10. Luo, W. T., Chang, C. L., Huang, T. W., & Gautama, M. S. N. (2025). Comparative effectiveness of netupitant-palonosetron plus dexamethasone versus aprepitant-based regimens in mitigating chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. The Oncologist, 30(2), oyae233. doi: 10.1093/oncolo/oyae233.

11. Kennedy, S. K. F., Goodall, S., Lee, S. F., DeAngelis, C., Jocko, A., Charbonneau, F., … Jerzak, K. J. (2024). 2020 ASCO, 2023 NCCN, 2023 MASCC/ESMO, and 2019 CCO: a comparison of antiemetic guidelines for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer, 32(5), 280. doi: 10.1007/s00520-024-08462-x.

12. Shirley, M. (2021). Netupitant/palonosetron: a review in chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Drugs, 81(11), 1331–1342. doi: 10.1007/s40265-021-01558-2.

13. Zhu, H., Huang, S., & Hu, X. (2025). Neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists in the current management of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Frontiers of Medicine, 19(4), 600–611. doi: 10.1007/s11684-025-1140-8.

14. Meyer, T. A., Habib, A. S., Wagner, D., & Gan, T. J. (2023). Neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Pharmacotherapy, 43(9), 922–934. doi: 10.1002/phar.2814.

15. Theodosopoulou, P., Rekatsina, M., & Staikou, C. (2023). The efficacy of 5HT3-receptor antagonists in postoperative nausea and vomiting: the role of pharmacogenetics. Minerva Anestesiologica, 89(6), 565–576. doi: 10.23736/S0375-9393.22.16983-X.

16. Thomas, A. G., Stathis, M., Rojas, C., & Slusher, B. S. (2014). Netupitant and palonosetron trigger NK1 receptor internalisation in NG108-15 cells. Experimental Brain Research, 232(8), 2637–2644. doi: 10.1007/s00221-014-4017-7.

17. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (2025, January 15). Palonosetron. In Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567877.

18. European Medicines Agency (2015). Akynzeo: EPAR — Product Information. Retrieved from http://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/akynzeo. doi: not available.

19. Navari, R. M., Binder, G., Bonizzoni, E., Clark-Snow, R., Olivari, S., & Roeland E. J. (2021). Single-dose netupitant/palonosetron versus 3-day aprepitant for preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a pooled analysis. Future Oncology, 17(23), 3027–3035. doi: 10.2217/fon-2021-0023.

20. Raedler, L. A. (2015). Akynzeo (netupitant and palonosetron), a dual-acting oral agent, approved by the FDA for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. American Health & Drug Benefits, 8(Spec Feature), 44–48. PMID: 26629265; PMCID: PMC4665070.

21. State Register of Medicinal Products of Ukraine. Інформаційний бюлетень. Retrieved from http://www.drlz.com.ua/ibp/ddsite.nsf/all/shlist?opendocument (retrieved: 12 January 2026).

22. Behbahany, K., & Bubalo, J. (2021). Capsule-related dysphagia and the use of netupitant/palonosetron (Akynzeo) capsules — a report of two cases and a solution. Journal of Oncology Pharmacy Practice, 27(5), 1284–1286. doi: 10.1177/1078155220965671.

23. Navari, R. M., & Bonizzoni, E. (2025). NEPA (netupitant/palonosetron) for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in patients receiving highly or moderately emetogenic chemotherapy who experienced breakthrough CINV in cycle 1 of chemotherapy: a phase II clinical trial. Cancer Medicine, 14(7), e70549. doi: 10.1002/cam4.70549.

24. Celio, L., Cortinovis, D., Cogoni, A. A., Cavanna, L., Martelli, O., Carnio, S., … Bria, E. (2022). Evaluating the impact of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting on daily functioning in patients receiving dexamethasone-sparing antiemetic regimens with NEPA (netupitant/palonosetron) in the cisplatin setting: results from a randomized phase 3 study. BMC Cancer, 22(1), 915. doi: 10.1186/s12885-022-10018-3.

25. Zhang, H., Zeng, Q., Dong, T., Chen, X., Kuang, P., Li, J., … Ji, J. (2023). Comparison of netupitant/palonosetron with 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 receptor antagonist in preventing of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Frontiers in Oncology, 13, 1280336. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1280336.

26. Hui, D., Puac, V., Shelal, Z., Liu, D., Maddi, R., Kaseb, A., … Bruera, E. (2021). Fixed-dose netupitant and palonosetron for chronic nausea in cancer patients: a double-blind, placebo run-in pilot randomised clinical trial. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 62(2), 223–232.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.12.023.

27. Kwak, K., Park, Y., Kim, B. S., & Kang, K. W. (2024). Efficacy and safety of netupitant/palonosetron in preventing nausea and vomiting in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients undergoing R-CHOP chemotherapy. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 11229. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-62057-4.

28. Bubalo, J. S., Radke, J. L., Bensch, K. G., Chen, A. I., Misra, S., & Maziarz, R. T. (2024). A phase II trial of netupitant/palonosetron for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea/vomiting in patients receiving BEAM prior to hematopoietic cell transplantation. Journal of Oncology Pharmacy Practice, 30(2), 304–312. doi: 10.1177/10781552231173863.

29. Yeo, W., Lau, T. K., Kwok, C. C., Lai, K. T., Chan, V. T., Li, L., … Mo, F. K. (2022). NEPA efficacy and tolerability during (neo)adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 12(e2), e264–e270. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-002037.

30. Celio, L., & Aapro, M. (2024). Characteristics of nausea and its impact on health-related quality of life in cisplatin-treated patients receiving dexamethasone-sparing prophylaxis: an analysis of the LUNG-NEPA study. Supportive Care in Cancer, 32(3), 204. doi: 10.1007/s00520-024-08406-5.

31. Nashed, S. M., Morcos, R. K. A., Atif, M., Shehryar, A., Rehman, A., Kumari, R., … Jameel, S. (2024). Comparative efficacy of novel versus traditional antiemetic agents in preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting with moderate or highly emetogenic chemotherapy: a systematic review. Cureus, 16(10), e72774. doi: 10.7759/cureus.72774.

32. Nilsson, J., Piovesana, V., Turini, M., Lezzi, C., Eriksson, J., & Aapro, M. (2022). Cost-effectiveness analysis of NEPA, a fixed-dose combination of netupitant and palonosetron, for the prevention of highly emetogenic chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: an international perspective. Supportive Care in Cancer, 30(11), 9307–9315. doi: 10.1007/s00520-022-07339-1.

Адреса для листування:

Дунаєва Інна Павлівна

61022, Харків, просп. Науки, 4

Харківський національний медичний університет

E-mail: innadunaieva@gmail.com

Correspondence:

Inna Dunaieva

4 Nauky ave., Kharkiv, 61022

Kharkiv National Medical University

E-mail: innadunaieva@gmail.com

Leave a comment